Lithium volatility is sorting the battery industry.

The winners already know who they are.

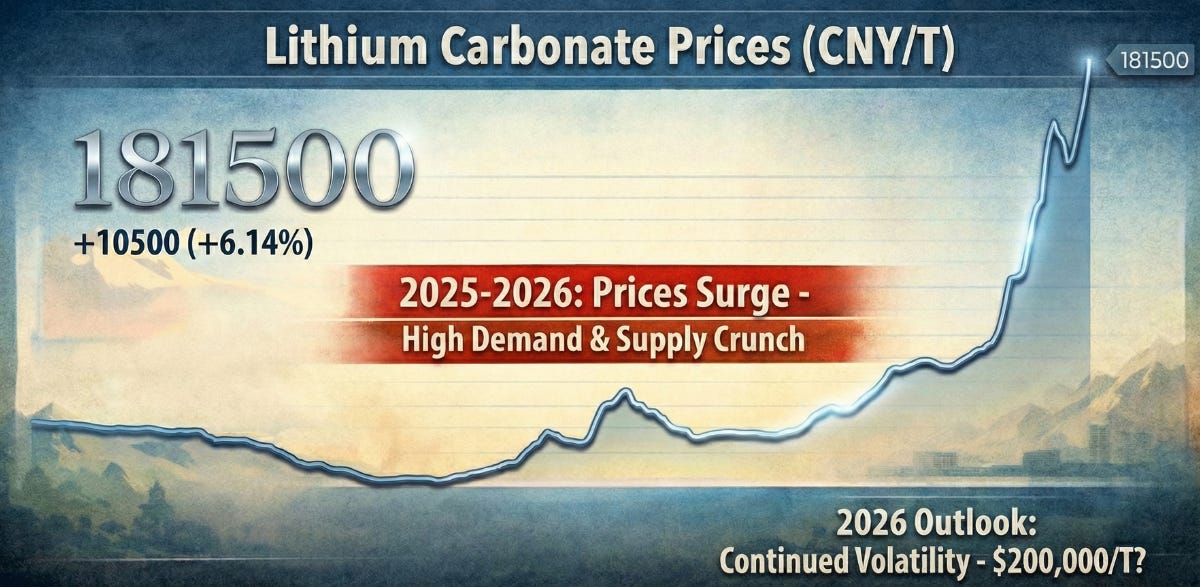

On January 26, lithium carbonate was quoted at CNY 181,500/t ($26,000/t).

That’s up 130% year-over-year. Since September alone, spot prices have risen 73%.

Meanwhile, battery pack prices kept falling. BNEF reported the global average at $108/kWh in 2025, down 8% from the prior year. Stationary storage fell to $70/kWh.

The gap exists because cathode and cell makers are cutting margins to hold volume and keep capacity running.

The question is how long that strategy holds.

Why the gap exists

Overcapacity defines the market.

According to McKinsey, global Li-ion battery overcapacity was approximately 900 GWh in 2025. In that environment, raising prices means losing volume. Losing volume means losing customers to competitors willing to run leaner.

CATL, BYD, EVE Energy, and other leaders are funding the gap from their balance sheets. They can afford to wait.

Smaller players cannot.

The strategy works as long as input cost spikes are temporary. If they persist, the math changes.

The supply shocks were expected

The lithium rebound did not arrive without warning.

CATL’s Jianxiawo mine has been shut since August 2025 after a key mining permit expired. Late-2025 reports pointed to a restart around the 2026 Spring Festival, but late-January reporting suggests the restart is delayed. There is still no confirmed resumption date.

In Jiangxi province, authorities announced plans to cancel 27 mining permits.

The DRC imposed export quotas on cobalt, cutting shipments by 48% starting in February 2025. Cobalt prices rose 131% from their annual lows.

China announced a VAT export rebate cut for batteries. The rebate falls from 9% to 6% between April 1 and December 31, 2026, then drops to zero from January 1, 2027, a schedule that pushed manufacturers to front-run lithium orders in early 2026.

Policy moved prices directly.

Permits, quotas, and rebate rules changed supply and buying behavior faster than the inventory buffer could absorb.

Demand is structural

Energy storage stopped behaving like a side market.

Global battery energy storage system (BESS) reached approximately 315 GWh in 2025, reflecting a nearly 50% year-over-year increase. Forecasts for 2026 indicate additions exceeding 450 GWh (Source: Rho Motion).

ESS demand jumped, and data centres added another pull on cells. AI is turning data centres into a new battery customer, on top of the grid-scale wave.

China is setting the pace.

China installed more battery capacity in December than the US deployed across the full year.

In 2025, BESS tenders in China hit new lows, as low as $63/kWh in some bids. If lithium stays elevated, that price floor becomes harder to hold through 2026.

The demand floor is rising. That matters when supply is constrained.

The buffer is eroding

The bill of materials extends beyond lithium.

Electrolyte costs moved faster than cathodes. LiPF₆ and vinylene carbonate rose over 140% and over 50% between July and November 2025. Copper foil and aluminum foil remain elevated.

Cell prices are already moving.

According to the latest SMM data as of January 23, 2026, NCM prismatic cells reached CNY 0.53/Wh ( ~ $76/kWh), reflecting a ~10% month-over-month increase. NCM pouch cells averaged around CNY 0.525/Wh ( ~ $75/kWh), up ~10-15% month-over-month.

LFP cells for EVs rose to CNY 0.45/Wh (about $65/kWh), a roughly 29% month-over-month jump. Further small increases are expected as input costs, including lithium, keep rising.

Beijing’s policy shift reinforces the direction.

The Central Economic Work Conference in December called for curbing “involutionary” competition, the official term for margin-destroying price wars.

Policy is now aligned with restoring profitability, not defending volume at any cost.

Cell makers can win individual pricing battles. They cannot hold the entire supply chain below cost indefinitely.

The upstream gap

The lithium rebound traces back to choices made during the crash.

When prices fell below $10,000 per tonne in 2023–2024, upstream investment collapsed.

Western lithium projects were shelved, placed into care and maintenance, or delayed indefinitely. Greenfield developments that required higher prices to justify capital stopped advancing.

Chinese producers with lower cost structures survived. But even in China, expansion slowed. The economics did not support new capacity at depressed prices.

Keep in mind that a mine takes years to develop, unlike a lithium refinery, which can be built and ramped much faster.

That underinvestment is now visible in spot markets.

Analysts now agree the lithium market is tightening, but they disagree on how big the squeeze will be. Morgan Stanley sees a global lithium carbonate equivalent (LCE) shortfall of about 80,000 tonnes in 2026. UBS expects a smaller shortfall of about 22,000 tonnes.

The supply that should have arrived in 2026–2027 was never funded. The pipeline is thinner than the demand projections assumed.

Cell manufacturing followed a different path.

Chinese cell makers continued expanding through the downturn. The capacity overhang that now absorbs input cost shocks exists because cell investment never paused.

The mismatch matters.

Upstream supply is constrained and slow to respond. Downstream capacity is oversupplied, but compressing margins.

The system is tighter at the top and looser at the bottom.

Sodium-ion finds its moment

Lithium’s rebound reopens a door.

CATL first unveiled sodium-ion technology in 2021, but slowed commercialization as lithium prices fell. At CNY 80,000 per tonne (~$11,500/t), sodium-ion struggled to compete.

At CNY 181,500/t ($26,000/t), the calculus changes.

In April 2025, CATL launched its Naxtra sodium-ion battery brand, reaching 175 Wh/kg energy density. That approaches LFP performance.

At its December 2025 supplier conference, CATL announced large-scale deployment across passenger EVs, commercial vehicles, battery swap systems, and energy storage starting in 2026.

Sodium is abundant, cheap, and not concentrated in the same geographies as lithium.

Whether sodium-ion scales fast enough to matter in 2026 is uncertain. But the conversation has restarted because the price signal changed.

Vertical integration pays off again

When input costs were falling, vertical integration looked like an expensive distraction.

Why own mines and recycling operations when suppliers compete to offer lower prices?

That logic is reversed.

BYD and CATL both built vertically integrated supply chains over the past decade.

BYD controls lithium resources, cathode production, cell manufacturing, and pack assembly. CATL owns lithium and nickel mines and controls Brunp, its recycling and cathode materials subsidiary.

Both companies can absorb input cost shocks internally. Price increases move between divisions rather than across negotiating tables.

The companies facing margin pressure are the ones without this structure.

Cell makers dependent on spot markets or short-term contracts absorb every price spike directly. They have no internal buffer.

Western battery companies that are not vertically integrated and have not locked in lithium supply at favorable prices will be under even more pressure.

The cost gap between China-made cells and European-made cells is already large. If materials costs keep rising, competing gets even harder, especially against Asian players with integrated supply chains.

Vertical integration fell out of fashion when prices only went down.

It matters again when they don’t.

This is a regime question

For most of the past decade, battery prices moved in one direction.

Manufacturing scale set the pace. Input costs fell or stayed flat. Learning curves compounded.

That regime assumed an abundant upstream supply. It assumed policy stability. It assumed Chinese producers would keep absorbing cost shocks indefinitely.

Each assumption is now under pressure.

Lithium supply is tighter than capacity figures suggest. Policy is shifting toward profitability over volume. Cell makers are passing through what they can no longer absorb.

The question is whether the change is temporary or structural.

If lithium stabilizes and supply recovers, the old regime resumes. Overcapacity reasserts itself, and prices fall.

If supply constraints persist and costs continue rising, the regime shifts.

Materials reassert pricing power. The floor moves higher.

Where instability sits

OEMs feel lithium first because cathode and cell makers cannot absorb rising input costs forever. The bill shows up with a lag, then all at once.

If lithium keeps climbing on this trajectory, OEM M&A teams will start dusting off “strategic” lithium investments again.

The problem is structural: public OEMs optimize for the next quarter, not the next cycle. They chase what looks urgent, and usually arrive late.

Volatility punishes rigidity.

When the price floor is unclear, flexibility becomes an asset.

Procurement structures that can move, chemistry optionality, and real supplier diversification matter more than squeezing another 1% out of today’s contract.

What this changes

The gap between lithium prices and battery prices was filled by margin compression.

That funding source is not unlimited.

Cell prices are rising. Electrolyte costs are elevated. Policy is discouraging further absorption. Sodium-ion is finding commercial traction. Vertical integration is paying dividends again.

The overcapacity that held prices down is still real.

But the willingness to defend it at any cost is fading.

Lithium volatility will persist as long as end-market demand stays uneven and hard to forecast.

McKinsey’s battery demand outlook implies the underlying pull keeps rising fast, from about 2000 GWh in 2025 to roughly 4,200 GWh by 2030, and around 6,800 GWh by 2035.

That trajectory means one simple thing: the system needs more lithium, and any mismatch between new supply and real-world demand swings will keep prices unstable.

The same thing happens with other materials, like copper.

If you find this kind of analysis useful, you may also be interested in two standalone resources I’ve built alongside the newsletter.

brilliant article explains lithium industry supply chain perfectly. we can also look at it from the lens of Nassim Taleb lens fooled by randomness - China did not take into account the upstream would be squeezed they extrapolated the current situation of industry - the lindy effect. the randomness of upstream squeeze

Really cool perspective! Do you think this will lead towards more long-term offtake deals?

A fun time to be in the mining space, some of my thoughts on the Mining Renaissance and Lithium specifically: https://gennaroliccardo.substack.com/p/the-mining-renaissance-volume-1-lithium